Introduction

We are an international coalition of public policy research institutes and think tanks that believes that collaboration, open trade and innovation is crucial to the response to Covid-19.

As the 2020 World Health Assembly re-convenes in Geneva, we urge governments to commit to simple reforms that will accelerate access to medicines, including those in the process of being developed for Covid-19. These reforms will have benefits that last beyond the current pandemic, increasing access to medicines for all.

Reduce unnecessary medicine costs by:

- Reducing taxes

- Abolishing tariffs

- Eradicating other trade barriers

Accelerate access to medicines by:

- Simplifying the drug approval process

- Modernising government medicine reimbursement decision-making

- Promoting genuine free trade in medicines

- Supporting the innovation system

1. Reduce unnecessary medicine costs

In the majority of developing countries, most healthcare costs are met directly out of pocket due an absence of functioning healthcare insurance and delivery. To improve access to medicines, governments should take steps now to remove unnecessary medicine price inflators, many of which are self-imposed.

1.1 Abolish tariffs on medicines

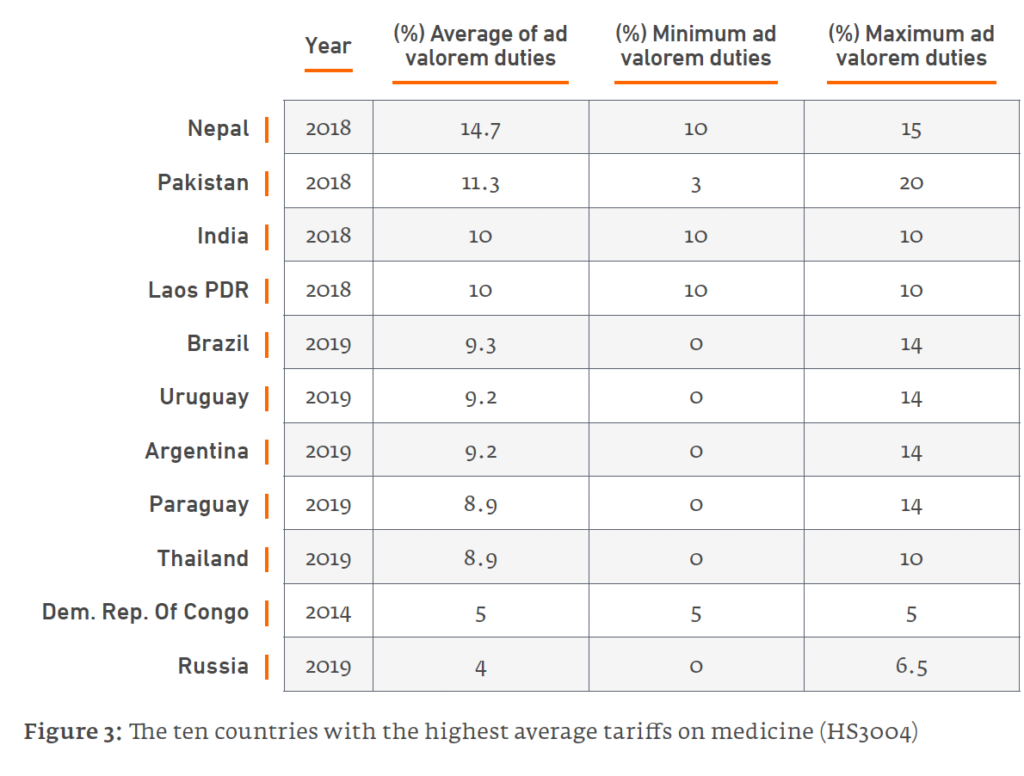

All countries need access to medicines and vaccines as cheaply as possible. Yet governments raise their price by levying needless import tariffs:

- At 20%, Pakistan boasts the highest rate globally. The South Asian trio of Nepal, Pakistan and India have the world’s top three tariff rates (10% in India). Latin America is another medicines tariff hotspot, with Argentina and Brazil levying average tariffs of close to 10% (Figure 1).

- While most countries enjoy tariff-free regimes for vaccines, certain others needlessly inflate their price through import tariffs. India again tops the table globally with vaccine tariffs at 10%. Pakistan and Bolivia are among a clutch of countries that impose vaccine tariffs of 5%.

Pharmaceutical manufacturing value chains are increasingly globalised; even low tariffs have a cumulative impact on a product’s end price, ultimately paid by patients. Abolishing these tariffs would save patients up to US$6.2bn in China, US$2.8bn in Russia, US$2.6bn in Brazil, US$737m in India, and US$252 in Indonesia.

In the context of Covid-19, some countries have shown leadership by exempting related medicines, vaccines and medical supplies from import duties and taxes including Pakistan, Brazil, Colombia and Norway.

Although a positive step, many of these reforms are only temporary. They create uncertainty for exporters over the long-term direction of individual markets and undermine preparation for future pandemics. Further, they only cover a narrow sub-section of medicines, when all medicines are “essential” to those who need them.

Policy recommendations

Governments should commit to permanent tariff reductions in medicines and vaccines via legally binding WTO commitments.

- Non-members should join the WTO Pharmaceutical Tariff Elimination Agreement (“Zero for Zero” initiative).

- If this is not possible, countries that still levy tariffs should unilaterally abolish them.

1.2 Eliminate other taxes on medicines

In many countries domestic taxes can make up 20-30% of the final price people pay for medicines. Countries at all spectrums of economic development apply VAT on medicines. Other taxes include state excise duty, stamp duty, community tax and other fees. In lower and middle-income countries, the range of total tax is 5%-34%. These taxes are regressive, undermine access to medicines and generate little revenue (between 0.03% and 1.7% of total tax revenue).

Policy recommendations

- Governments should review taxes imposed on medicines with a view to rationalisation, or preferably, abolition.

- Covid-19 therapeutics and vaccines should be made available tax free.

1.3 Eradicate trade inefficiencies that drive up medicine costs

Medicine prices are increased, and access delayed, by Non-Tariff Measures (NTMs) such as inefficient customs procedures, cumbersome export and import procedures, administrative red-tape, hidden taxes, congestion fees and a generally sub-optimal trade infrastructure.

For medicines, NTMs also include burdensome labelling and packaging requirements, the need for importers to have multiple permits and licenses, and the requirement that imported medicines must pass through specific ports. These barriers are often higher in developing countries.

The time and effort involved in navigating these procedures adds to the costs of trade in medicines, costs which are ultimately passed onto patients. For smaller markets, manufacturers might consider it unworthwhile to export, meaning that patients will enjoy fewer types of medicine and less competition.

Policy Recommendations

- Governments should examine the existing stock of NTMs to eliminate superfluous regulations.

- Official forms and guidelines should be made available in English online

- Measures reducing NTMs should be included in Free Trade Agreements

- All signatories to the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement should abide by their commitments to reduce NTMs.

- Governments should create priority lanes at borders for essential medical supplies, as Brazil has done for Covid-19 products.

2. Accelerate access to new medical technologies and medicines

Innovative vaccines and therapeutics will be essential to ending the Covid-19 pandemic, and also to tackling the rising burden of non-communicable diseases that accompany ageing and more affluent populations throughout the world.

Sadly, patients in developing countries wait longer for these innovations. There are several reforms which could address this problem.

2.1 Speed up the process of drug regulatory approval

Patients face long waits for new treatments while waiting for national drug regulatory authorities to approve them, even if they have already been declared safe and efficacious by a stringent regulatory authority such as from the US food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicines Agency (EMA). Regulatory delays are unconscionable particularly in the context of new Covid-19 medicines and vaccines.

- The worst delays are in sub-Saharan Africa, where patients must wait four to seven years for their regulators to approve medicines already approved by the FDA or EMA.

- There are delays 0f around two years in Brazil and Colombia, and average delays of 400-500 days in India, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea and Malaysia. Indonesian patients must wait for nearly three years and Chinese patients over two years (Figure x).

The World Health Organization says that these delays are caused by overly complicated guidelines and lengthy assessment periods, and backlogs due to resource constraints. Many regulators in developing countries duplicate work already done by more mature regulatory authorities.

Policy Recommendations

- Developing countries should strengthen regional agreements relating to mutual recognition procedures for regulatory approvals in order to accelerate access to medicines (e.g., the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, the European Union Mutual Recognition Procedure, and the African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization Program)

- National regulatory authorities should accept clinical trials data generated by mature foreign regulatory agencies except where there is a compelling public health

2.2 Get medicines onto public formularies more quickly

Patients are denied access to life saving medicines waiting for government agencies to decide if they can be provided by the public sector. Once a medicine has received regulatory approval, it cannot be adopted by the public health system until the government decides whether it can be included on the National Formulary List and if so at what rate it will be reimbursed. These decisions can take several years, further delaying access to medicine and undermining patient choice. Such delays would be particularly damaging for new Covid medical technologies.

Policy recommendation

- Governments should update National Formularies and reimbursement lists dynamically, instead of publishing new lists annually or less frequently.

2.3 Promote open markets in medicines

Many countries try to promote industrial and economic development by requiring companies to locate parts of their value chains within their borders in return for license to operate. Examples include banning the importation of drugs that have a locally-manufactured equivalent; prioritising local companies in state procurement tenders; and dictating where companies to locate manufacturing facilities in return for market access.

Such “localised barriers to trade” (LBTs) balkanise value-chains and drive up the end price of medicines by requiring firms to create multiple and duplicative local manufacturing plants. They also reduce numbers of medicine suppliers, leading to higher prices, fewer choices and shortages.

In the context of Covid-19, such regulations could stand in the way in the rapid manufacture and global distribution of new vaccines and therapeutics.

Policy recommendation

- WTO members should work towards a stronger role for the WTO in enforcing existing laws regarding local content requirements and establish a comprehensive database to track LBTs worldwide.

3. Support innovation, including intellectual property rights, during the Covid-19 crisis

Biopharmaceutical innovation will play a pivotal role in resolving the Covid-19 crisis, both in the form of new treatments that can mitigate the worst effects of the disease, and ultimately a preventative vaccine. Such life-saving technology is less likely to be forthcoming if governments sacrifice intellectual property (IP) rights, even before such technologies have been invented.

IP rights facilitate cooperation and the sharing of proprietary data, know-how and technology between different and often competing companies and organisations, both domestically and across borders. They also provide an incentive for the private sector to commit and share resources with competitors to manufacture billions of doses and distribute them globally in a short space of time. Even if IP rights were confiscated, no government has the capacity to manufacture novel, complex vaccines and medicines at vast scale. Cooperation with rights holders is surely preferable to confiscation.

The IP system is working well in the pandemic. There are now over 1240 active clinical trials on 534 unique therapies, and there are 43 unique vaccines being tested.

There is no evidence that IP rights will pose a barrier to access, as most companies working in this area have stated any new products will be available on a non-profit basis. This is welcome, although it is important as many organisations as possible are incentivised to commit their resources to COVID-19 treatments and vaccines through the IP system.

Policy recommendations

- Now is not the time to undermine IP rights. They underpin the global medicine innovation ecosystem. Governments should therefore commit to cooperating with the private sector in the quest for Covid-19 treatments and vaccines.