1 MINUTE QUICK READ

- Colombia is on the cusp of passing the final test for OECD accession, membership of which would confer enormous diplomatic and economic prestige.

- Colombia has come a long way economically, but needs to focus more closely on innovation in order to overcome significant weaknesses in productivity that are holding its economy back.

- Instead of bolstering intellectual property rights (IPRs) to promote innovation, the government is undermining them in a bid to close structural deficits in its healthcare system caused by excessive litigation and growth in demand.

- Undermining basic market institutions such as IPRs through compulsory licenses will hurt the country’s innovative potential and investment.

- It is also behaviour more normally associated with countries with governance far below OECD standards, typically in the midst of health crises such as HIV.

- Threatening to override property rights to secure discounts is an aberration from OECD norms, where pricing is normally determined through negotiation and collaboration.

- It is imperative for the future credibility of the OECD that it maintains its current high requirements for new members.

The OECD, whose 35 members include the world’s richest nations, has significant influence on global trade and economic policy. In applying to join, Colombia is signalling its intention to promote market-friendly policies and abide by the organization’s standards for transparency and tax rules. Accession to the OECD will mark the close of Colombia’s recent turbulent history, permanently changing the country’s brand for the better.

Membership of the OECD is a prize worth striving for. It provides a “seal of approval” that marks members out them out as liberal democracies that respect property rights and operate open markets under a strong rule of law. The prestige of OECD membership is accompanied by high investor confidence, better access to finance and more credibility and clout with partners when negotiating trade deals.

But the OECD also has the important role of encouraging countries to turn away from economically damaging socialistic or populist policies towards market-friendly reforms, liberal values and high standards of governance. OECD members undergo a constant process of policy ‘peer- review’, in which domestic policies are compared to international best-practice and recommendations given for improvement. This rationale was behind the OECD’s decision in the early 1990s to extend membership to the former Soviet countries of eastern Europe, in order to embed their transition to market economies. Similar thinking is behind the decision of current OECD head Angel Gurria to encourage accession amongst Latin American countries, several of whom have recently rejected economic populism in favour of liberal market economies.

On the face of it, Colombia should be a straightforward candidate for accession. Over the last two decades, deep structural and macroeconomic reforms have allowed Colombia to make impressive progress in reducing poverty, with only 5.5% of the population living in extreme poverty compared to 16.2% in 2000.

Over the same period, Colombia’s gross national income increased $97.7 billion to $286 billion (although growth has tailed off in the short-term due to global falls in commodity prices). It is now the fourth largest economy in Latin America, and an increasingly important regional economic, cultural and diplomatic power. The strong diplomatic backing of the United States, who in February 2018 issued a strong statement of support,adds to Colombia’s case for OECD accession.

However, the support of the United States is not enough for a country to succeed in its application for OECD accession. Rather, applicants must demonstrate that they have put in place the reforms and structures that meet the high standards of governance required by OECD membership. Prior to accession, applicants must be approved by expert OECD committees across a range of policy areas. Colombia has made great efforts to pass these Committee tests, modifying a number of its laws and regulations to meet the OECD’s high standards. These reforms have borne fruit, with the employment, labour, and social affairs committees all issuing formal opinions supporting Colombia. The final hurdle is the trade committee, meeting in Paris in April 2018. Approval here will allow Colombia to proceed to the formalities of accession and join the global elite of nations.

But the Trade Committee should pause before it gives the rubber stamp to Colombia’s accession. Although the decision to open the accession process to new, non-European countries such as Colombia is a sensible recognition by the OECD that it must reflect global economic changes if it is to retain its legitimacy, that does not mean that standards for accession should be diluted or skipped over in order to meet this political objective. It is imperative for the future credibility of the OECD that is maintains its current high requirements for new members, otherwise the OECD “brand” would be devalued as a whole. This would be fatal for an organisation that relies on soft norms rather than hard laws to further its core objectives.

The accession of Latin American countries where governance has historically been volatile and the rule of law weak poses a challenge to the organisation. Peru and Argentina are at the beginning of their accession process and therefore have some time to demonstrate the commitment to liberal democracy, good governance and the rule of law that are the hallmarks of OECD member countries. Colombia on the other hand is in the final stages of the its accession process, and despite having travelled a long way since the 1990s, still has certain governance issues that would be out of place in most OECD members – particularly around the treatment of intellectual property rights, a cornerstone economic right for OECD countries. The question for the OECD is whether Colombia is yet ready to join its ranks. This is an important question, the answer to which will impact the organisation’s credibility, brand and eventually effectiveness for many years to come. This research note looks at the evidence.

Colombia OECD accession journey

To accede to the OECD, aspirant members must undergo a thorough review process in a wide range of policy areas to ensure they match up to the organisation’s high standards. At the start of the accession process, the OECD secretariat establishes an accession roadmap tailored for each new potential member, which details the policy areas which will be assessed, as well as a schedule. The roadmap is agreed by the OECD Council by consensus.

Colombia’s roadmap was agreed in 2013 and sets out the policy areas in which the government must engage with the OECD’s expert committees to demonstrate compliance with the OECD’s fundamental values, legal instruments, policies and practices. One major benefit of this process is that the accession process can act as a catalyst for positive domestic reform, improving governance and contributing to social and economic improvements. This process has been especially beneficial to Colombia, whose governance has historically been characterised by a high level or corruption, opacity and arbitrariness.

Colombia’s roadmap was agreed in 2013 and sets out the policy areas in which the government must engage with the OECD’s expert committees to demonstrate compliance with the OECD’s fundamental values, legal instruments, policies and practices. One major benefit of this process is that the accession process can act as a catalyst for positive domestic reform, improving governance and contributing to social and economic improvements. This process has been especially beneficial to Colombia, whose governance has historically been characterised by a high level or corruption, opacity and arbitrariness.

Notable reform highlights of Colombia’s accession journey include its 2013 signature of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, which extended existing laws against bribery of public official to the business realm. Colombia has also modernised its regulatory codes across the board to make them more transparent and less arbitrary, and increased the independence of regulators to make them less prone to political interference. Transparency and efficiency has also been improved through the creation of a centralised public procurement agency (Colombia Compra Eficiente), in line with OECD advice, which puts all tenders online and provides a new transparent framework for procurement. The OECD accession process has seen governance reforms of the country’s State- Owned Enterprises, an economically important sector for Colombia constituting 32% of national GDP. OECD-backed reforms include a new policy which ensures that SOEs and private enterprises receive equal treatment, and an end to the practice of filling the boards of SOEs with members of the executive branch, such as government ministers.

Questionable practices

Despite this positive agenda, Colombia continues with a number of questionable practices which undermine its bid for OECD membership. Trade unionists have complained of significant breaches of their rights by the government, for instance, and the OECD itself has observed that Colombia’s important mining sector continues to be subverted by criminals, resulting in human trafficking, illegal labour and environmental damage.

International businesses groups have complained about new policies and guidelines being introduced by the government without enough time for proper consultation; a truck scrappage scheme that acts as a de facto trade barrier; and concerns about regulatory procedures which cause delay in the market authorisation of new imported medicines. These are all significant concerns for businesses seeking to invest in Colombia.

Innovation – the OECD path to prosperity

The OECD’s latest economic assessment (May 2017) of Colombia shows the economy still has major weaknesses. The gap between rich and poor among the highest in Latin America, informality and gender gaps remain high, and social mobility is low. Years of armed conflict, burdensome local regulations and distortions in the tax system have created disparities in access to basic services across regions.

At the root of many of these problems is low productivity, which the OECD attributes to a combination of low skills; weak infrastructure; an underwhelming innovation performance exacerbated by low investment in R&D; and poor business-academia links. Further, the OECD states that Colombia needs to participate more in global value chains to increase the adoption of new technologies and drive productivity increases.

To achieve the increases in productivity necessary to underpin sustainable economic growth and close down regional disparities, innovation will be key. Innovation is recognised by economists as an important driver of economic growth, by allowing greater productivity: meaning that the same input generates a greater output. As productivity rises, more goods and services are produced by fewer resources – in other words, the economy grows. Innovation is a major contributor to economic growth, responsible for up to 50% of annual GDP growth in the United States, for example.

Writing in the 2013 OECD yearbook, the OECD director for science, technology and industry Andrew Wyckoff outlined the way in which OECD members increasingly rely on innovation and knowledge-based capital (intangible assets, like research, data, software and design skills, which capture or express human ingenuity) to drive productivity and economic growth.

“Knowledge-based capital allows countries and firms to upgrade their comparative advantage and position themselves in higher value-added industries, activities and segments of the global marketplace”, writes Mr Wyckoff. Further, “ageing populations and dwindling natural resources mean that growth in advanced economies will increasingly depend on knowledge-based increases in productivity,” he adds. And although in OECD countries like the United States and United Kingdom investment in knowledge-based capital has long outpaced investment in physical capital, “both China and Brazil are also making concerted efforts to develop knowledge-based capital to increase productivity and occupy higher-value segments in global production chains.”

Despite the centrality of innovation to growth, and the high store placed on innovation by OECD member countries, Colombia’s innovation system is still underdeveloped and lacks meaningful private sector participation. Colombia has very low rates of participation in global value chains – crucial to most modern economies – well below the OECD average and outperformed by many emerging markets. R&D expenditure is low at 0.2% of GDP, compared to 2.4% in the OECD. Colombian firms do not generally engage in innovation, with only a small portion of manufacturing firms introduce new products. Only 30% of total R&D is performed by the business sector, compared with 70% on average for OECD countries.

To make the transition from a commodity-dependent economy to a diversified high-income country more reflective of OECD membership, Colombia needs to pay greater attention to the policy frameworks required to encourage domestic innovation.

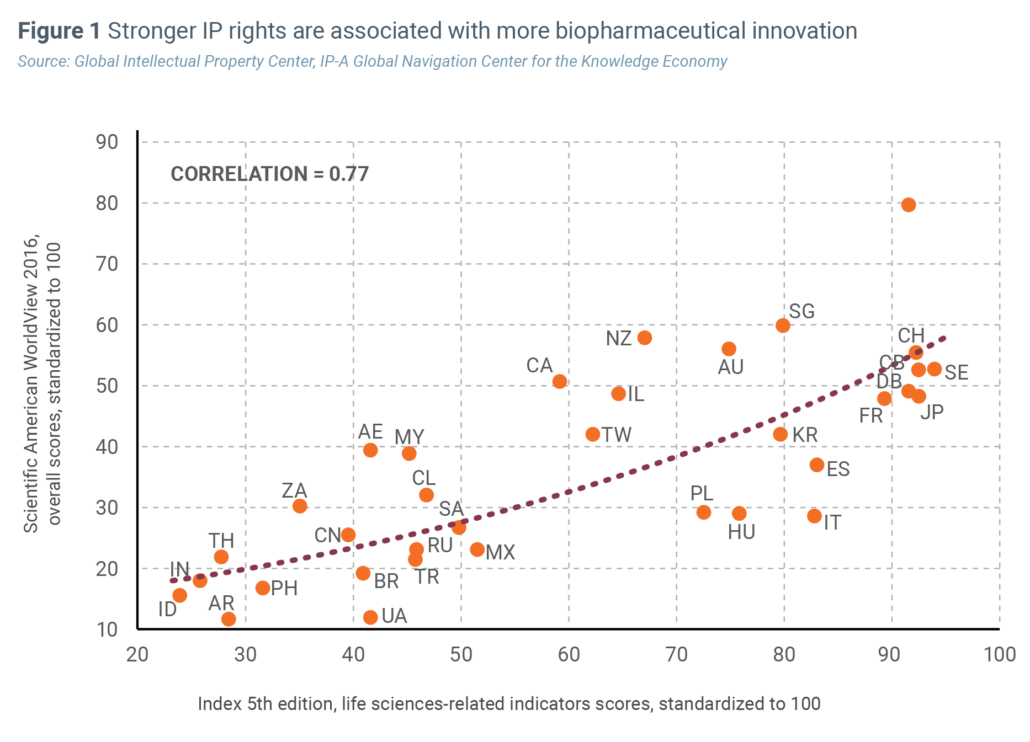

Alongside supportive regulatory policy, taxation and education, a functioning knowledge-based economy needs a strong framework for the protection of intellectual property rights, including clearly defined and easily enforceable patent rights. IPRs are particularly important for knowledge-intensive industries such as biopharmaceuticals, given the sector’s high upfront investment costs (€1.13bn to €2.44bn, according to various studies) and significant risk of research failure. Indeed, those countries that afford the highest levels of protection of IP perform the best in high-value added activities such as biopharmaceutical innovation (Figure 1).

Aside from their role in incentivising investment in R&D, IP rights such as patents fulfil a number of roles in the market-based system of innovation that are crucial for countries like Colombia, that are hoping to move up the value chain and develop significant indigenous innovative industries:

Aside from their role in incentivising investment in R&D, IP rights such as patents fulfil a number of roles in the market-based system of innovation that are crucial for countries like Colombia, that are hoping to move up the value chain and develop significant indigenous innovative industries:

- IP rights allow research collaboration between different organisations, increasingly important in an era in which innovation is conducted in a collaborative manner between large multinational companies, small companies, academic institutions and the public sector.

-

Patents help patients access new medicines faster. Numerous econometric analyses have found that stronger IP protections are associated with speedier launches of new drugs for countries at all stages of economic development; and conversely, weak IP rights being associated with new drug launch delays of many years.

-

Robust intellectual property protection drives Foreign Direct Investment, with the OECD finding that a one percent increase in the strength of patent protection equates to a nearly three percent increase in FDI across all countries.

-

Patents promote competition by sharing the knowledge behind an invention with the world. Patent applications, which must include detailed information about new products and processes, are freely searchable by the public – even before patents expire. This disclosure accelerates innovation and empowers potential competitors to design around inventions without re-inventing the wheel. This disclosure can help countries “catch-up” in the development of their innovative capacity.

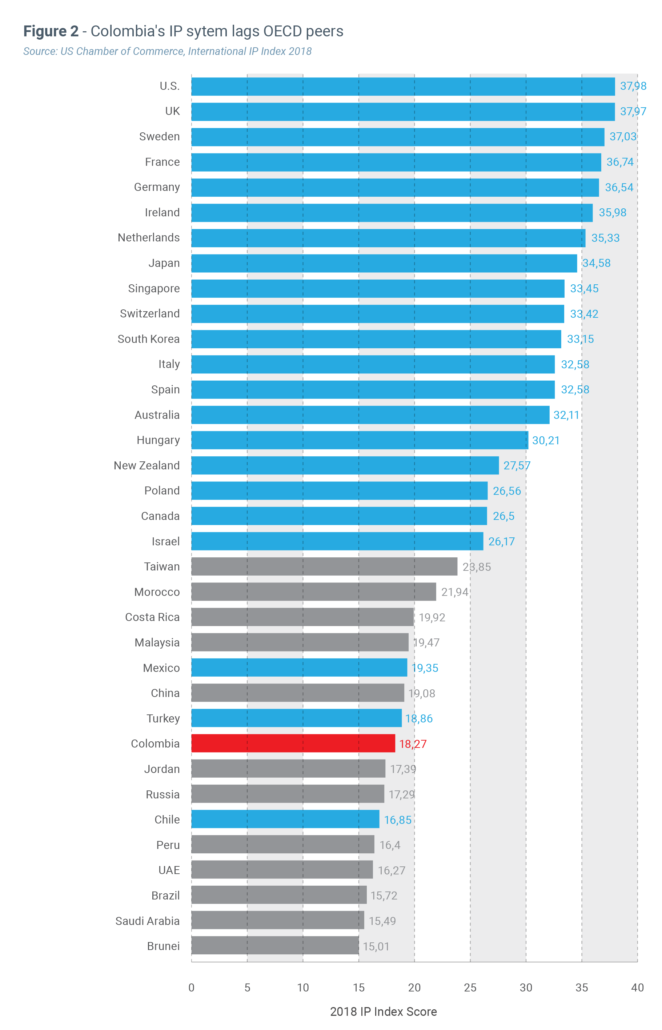

Despite the importance of innovation for economic growth, and the importance of IP for innovation, the OECD notes that Colombia’s IP system fails to leverage fully the innovative potential of the private, public and academic sectors.Other external evaluations of the quality and effectiveness of Colombia’s IP system show it to rank alongside Chile at the bottom of OECD countries in the quality and effectiveness of its IP frameworks, and outranked by China, costa Rica and Morocco (Figure 2).

Despite the importance of innovation for economic growth, and the importance of IP for innovation, the OECD notes that Colombia’s IP system fails to leverage fully the innovative potential of the private, public and academic sectors.Other external evaluations of the quality and effectiveness of Colombia’s IP system show it to rank alongside Chile at the bottom of OECD countries in the quality and effectiveness of its IP frameworks, and outranked by China, costa Rica and Morocco (Figure 2).

The Global IP Index, for instance, states that while Colombia provides a basic framework for major IP rights, and has taken recent steps to improve enforcement and streamline IP application procedures, there are still gaps in the copyright framework and difficulties in prosecuting IP infringements. On the biopharmaceuticals front, Colombia’s IP framework offers little beyond the minimum standards provided by the WTO TRIPS Agreement, negotiated over two decades ago before the mainstream adoption by the medical profession of modern biotechnological or precision medicines:

- Colombia offers no patent term restoration to compensate for regulatory delays, for instance, even though this fairly basic IPR is widespread amongst OECD countries

- Regulatory data exclusivity is only available for a period of five years, compared to 12 years in the Unites States, 11 years in the EU, and eight years in Canada and Japan.

- There is no early dispute resolution mechanism for patent infringements.

Such lacunae within its IP framework undermine Colombia’s overall potential as an investment destination and impede the ability of local innovators to leverage their intellectual property to grow and develop. While not a requirement of OECD membership, improvements to the country’s IP system will improve the innovative capacity of the economy, by attracting FDI from foreign knowledge-intensive industries, accelerating product launches and providing further opportunities for collaboration between local and international innovators.

Compulsory licenses can’t solve Colombian healthcare’s structural deficit

These shortcomings notwithstanding, it is Colombia’s Ministry of health’s recent measures against foreign intellectual property rights holders that really raise questions about the country’s compatibility with OECD membership, in particular its use of compulsory licenses to force deep and arbitrary discounts on patented medicines. The first instance was for a widely prescribed patented cancer medicine (imatinib) in 2016 and action is ongoing for an entire class of Hepatitis C medicines.

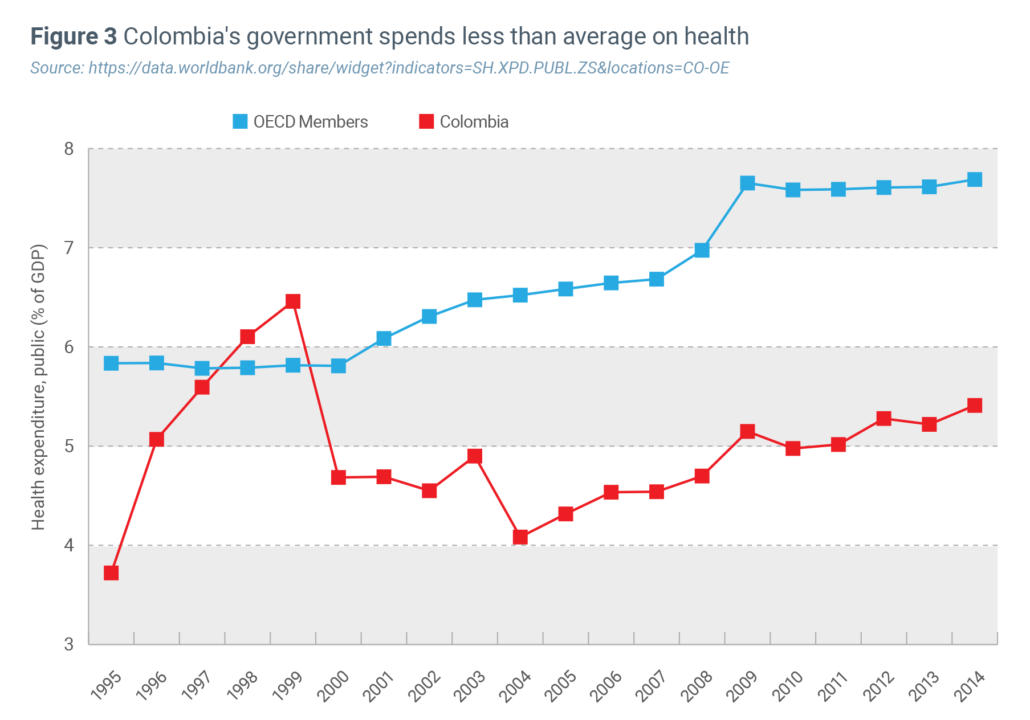

The Colombian government’s moves against the IPRs of patented medicines finds its origins in the health system’s decades of sustained financial pressure and fiscal deficit, which have been worsening in recent years. On top of an underinvestment in the health sector compared to other OECD countries the Colombian healthcare system finds itself under significant financial pressure, with allocations by government far lower than the OECD average (Figure 3). The 2015 introduction by the Colombian Government of a legal guarantee of the fundamental right to health for all citizens,has further complicated matters by placing additional financial demands on the system.

This reform has theoretically given 48 million Colombians a right to almost any drug or treatment registered in the country and prescribed by their doctor. As a result of this reform, patient groups and physicians frequently secure access to new medical technologies through litigation, rather than through Colombia’s established pricing and reimbursement mechanisms. According to research from the Colombian Ombudsman, over 118,000 court claims for health care provision were made in 2014. “Colombia has the most judicialised health care sector in the world,” according to Jaime Arias, president of the Colombian Association of Integral Medicine Companies (ACEMI). “There is pressure from the courts to provide high-end health care to all citizens, and the field of heath jurisprudence has grown rapidly.”

This reform has theoretically given 48 million Colombians a right to almost any drug or treatment registered in the country and prescribed by their doctor. As a result of this reform, patient groups and physicians frequently secure access to new medical technologies through litigation, rather than through Colombia’s established pricing and reimbursement mechanisms. According to research from the Colombian Ombudsman, over 118,000 court claims for health care provision were made in 2014. “Colombia has the most judicialised health care sector in the world,” according to Jaime Arias, president of the Colombian Association of Integral Medicine Companies (ACEMI). “There is pressure from the courts to provide high-end health care to all citizens, and the field of heath jurisprudence has grown rapidly.”

The expansion of coverage, to include ever greater varieties of new medical technologies, partly as a result of the judicialisation of the right to health, has outstripped the financial resources of the Colombian healthcare system, with deficits considerably worsening since 2005. Another problem has been the incorrect assumption made as part of reforms in the early 1990s that 80% of Colombians would be paying into the contributory system from their monthly salary as formal employees. However, more than half the country’s jobs continue to be in the informal economy, and as such subsidised coverage for a generous benefits package has expanded far faster than commensurate inflows of premiums or finance.The result has been a continuing structural deficit in the healthcare system that looks increasingly unsustainable – not least because the country spends only 6.8% of GDP on health – less than Mexico or Brazil.

It is against this backdrop of unchecked demand and insufficient financing that the government has found itself forced to take unorthodox policy measures to control healthcare costs – including the use of compulsory licenses as a tool to force down medicine prices.

It is against this backdrop of unchecked demand and insufficient financing that the government has found itself forced to take unorthodox policy measures to control healthcare costs – including the use of compulsory licenses as a tool to force down medicine prices.

Compulsory licenses have not been a feature of Colombian healthcare policy until 2016, when a government technical committee recommended to the government that a compulsory license for imatanib, a widely used patented oncology drug, would be in the public interest, citing the cost pressures on the health budget.Health Minister Alejandro Gaviria subsequently issued a declaration that it would be in the public interest for the government to lower the price, the first step towards a compulsory license. Although no compulsory license was eventually issued for the drug, its threatened use resulted in a significant price cut, calculated according to a methodology devised by the government.

A compulsory license is in effect an abrogation of property rights and a major market intervention that sends a signal to outside market players that the country is a risky proposition for investment, collaboration or product launch. As such, few countries have been prepared to issue compulsory licenses except in public health emergencies or as a measure of last resort, and certainly not to fulfil industrial or political objectives (which are in any case arguably contrary to the permitted grounds for a compulsory license under article 31 of the WTO TRIPS Agreement). In the case of Imatinib, there was a clear political element to the declaration of public interest, with the Minister of Health citing changes in domestic demand as a justification: “Technological pressure and high drug prices have brought the health-care system to a financial crisis…Colombia is a paradigmatic case of a middle-income country, with a growing health system and with rising expectations from its middle class, which cannot pay high prices for new drugs.”

Although Colombia’s otherwise hospitable investment climate may have suggested the situation with Imatinib was an aberration, recent developments suggest otherwise. In December 2017 the Ministry of Health issued a resolution to determine whether a declaration of public interest should be pursued against an entire class of medicines for Hepatitis C, a viral infection which affects around 0.66% of the Colombian population.As in the case of Imatinib, a declaration of public interest would pave the way for compulsory licenses for these medicines, should the government so decide. Again, the government hopes to use this mechanism to secure significant price cuts in order to save money for its healthcare system, even though one of the largest rights-holders of these medicines has a widely-praised access initiative based on voluntary licensing. This particular initiative has resulted in significantly reduced prices for over 100 low and middle-income countries.

The threat of compulsory licenses creates tremendous market uncertainty for biopharmaceutical companies. If a country regularly resorts to or threatens compulsory licenses, innovative biopharmaceutical companies will be unlikely to consider it a priority country for the launch of new medicines. Without a local launch of the innovative product, generic companies may not be able to obtain the necessary regulatory approvals to sell their products, unless they are willing to shoulder this significant cost themselves. Generic companies might also be unable to afford the significant costs of medical education necessary for the appropriate use of the products by the healthcare community. Widespread use of compulsory licenses may therefore deny or delay patients’ access to innovative products, and hinder the introduction of generic versions in the longer term.

In addition, frequent use of compulsory licenses could force companies to withdraw their investments in pharmaceutical supply chains in countries that exercise them. This could lead to big gaps in drug coverage, and paradoxically higher prices as less efficient distribution systems will inevitably drive up the retail price of drugs.

In addition, frequent use of compulsory licenses could force companies to withdraw their investments in pharmaceutical supply chains in countries that exercise them. This could lead to big gaps in drug coverage, and paradoxically higher prices as less efficient distribution systems will inevitably drive up the retail price of drugs.

At any rate, using coercive strategies to secure discounts, such as the threat of compulsory licenses, is out of step with the norms prevalent amongst OECD members. Compulsory licenses have only been used sparingly in the past, in the majority of cases by non-OECD countries for anti-retroviral medicines in the 1990s and 2000s. A few middle-income countries have used them on occasion as a negotiating tool to secure drug price reductions, notably Brazil for HIV medicines in the mid 2000s, although – apart from Colombia – such behaviour has not been seen for some time on the international stage. There is no instance of an OECD country following through on a compulsory license for a medicine.

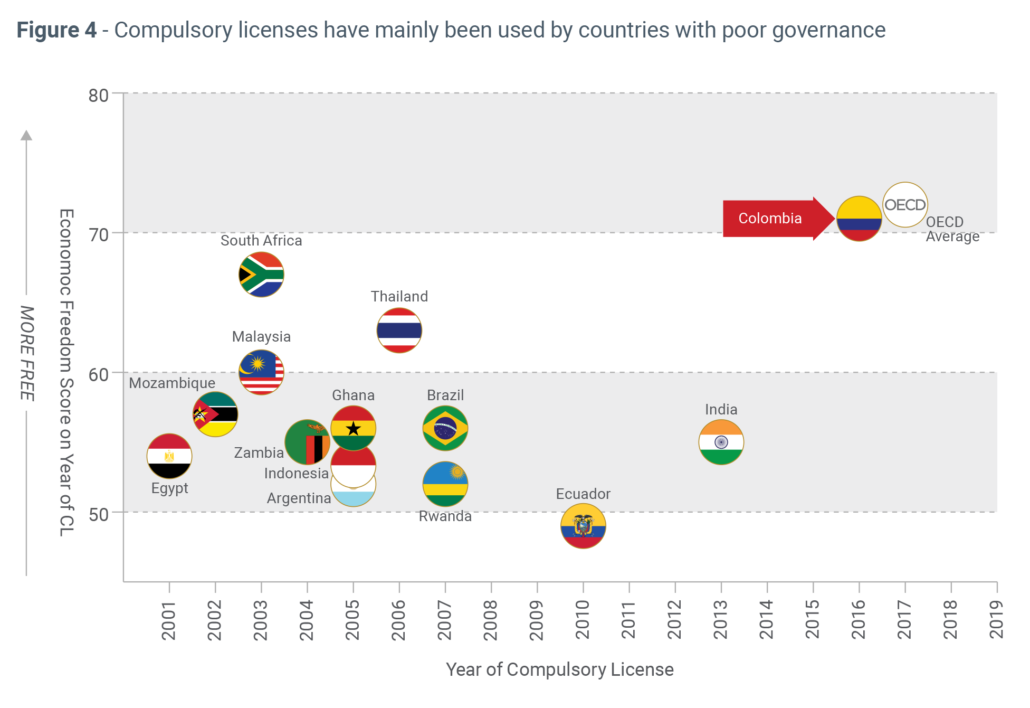

Rather, compulsory licenses, with the occasional outlier, have been mostly used by countries with varying degrees of illiberal and dysfunctional governance, as measured by the Index of Economic Freedom. Countries with a low score on this index have varying degrees of repressive governance, for example a lack of respect for economic fundamentals such property rights and the rule of law (Figure 4). Although Colombia generally scores highly in the Index of Economic Freedom, its undermining of property rights to obtain access to proprietary health technologies is out of step with its generally market-friendly governance, and is behaviour more typical of countries with far weaker governance and respect for market institutions.

Rather, compulsory licenses, with the occasional outlier, have been mostly used by countries with varying degrees of illiberal and dysfunctional governance, as measured by the Index of Economic Freedom. Countries with a low score on this index have varying degrees of repressive governance, for example a lack of respect for economic fundamentals such property rights and the rule of law (Figure 4). Although Colombia generally scores highly in the Index of Economic Freedom, its undermining of property rights to obtain access to proprietary health technologies is out of step with its generally market-friendly governance, and is behaviour more typical of countries with far weaker governance and respect for market institutions.

In fact, OECD countries tend to resolve drug pricing issues through negotiation and collaboration, rather than through coercion and confiscation, recognising that investment in R&D should be fairly rewarded in order to promote continued innovation. The OECD’s latest recommendations on how members should approach drug price negotiations makes no mention of the abrogation of intellectual property rights, for instance, but rather suggests a range of non-coercive approaches to drug price negotiation and reimbursement.

Conclusion

In its 2017 economic assessment of Colombia the OECD criticised Colombia for not making growth more inclusive. “Years of armed conflict, stringent local regulations and distortions in the tax system have created disparities in productivity and access to basic services across regions”, the OECD stated. Although the country offers universal healthcare coverage, and out of pocket payments are among the lowest in Latin America, those (typically poorer) Colombians without enhanced coverage in their multi-tier health care system face long waits for treatment and medicine, according to the OECD.32 Quality of healthcare is poor, with survival outcomes for a range of cancers well below the OECD average. Poor accountability and misaligned incentives amongst healthcare insurers and providers mean that much money is wasted, says the OECD. Undermining intellectual property rights will do little to rectify these deep systemic problems, but will do great harm to the country’s reputation as a safe investment destination, not least because other knowledge-based industries will look at the country in a new, negative light.

The fact that Colombia appears to have settled on a course of coercive an unorthodox policy measures in order to reduce its medicines bill is difficult for the OECD from a number of perspectives.

For existing members of the OECD, membership provides international credibility and clout that permit greater influence on the world stage, as well as providing reassurance to potential investors that governance will be transparent, predictable and market-friendly. Further, offering the prize of membership is a powerful incentive to encourage and entrench market reforms in aspirant countries, particularly for those regions that have had difficult economic pasts.

For existing members of the OECD, membership provides international credibility and clout that permit greater influence on the world stage, as well as providing reassurance to potential investors that governance will be transparent, predictable and market-friendly. Further, offering the prize of membership is a powerful incentive to encourage and entrench market reforms in aspirant countries, particularly for those regions that have had difficult economic pasts.

Colombia has certainly made great economic progress in recent decades through market-friendly reforms that have helped it a long way down the OECD accession process. But for OECD membership to remain meaningful, it is imperative that standards are maintained and significant problems with governance are not glossed over. Potential members must fully adhere to the norms and standards that mark out OECD countries as safe investment destinations, characterised by the highest standards of governance. A bedrock for existing OECD countries is respect for basic market institutions, notably property rights, which are fundamental to any functioning market economy. A commitment to transparent market economy principles are a fundamental value of OECD membership and should be reflected in decision-making around Colombia OECD accession.

The Colombian government’s willingness to interfere with intellectual property rights in order address partly self-inflicted financial problems in its healthcare system therefore suggests it is not ready for membership of the OECD. OECD were to admit a country that displays a populist attitude to property rights, it would be diminished as an organisation.