Introduction

The Covid pandemic has demonstrated that the biopharmaceutical innovation ecosystem works. In highly compressed timelines, existing drugs have been repurposed to treat Covid, and new drugs invented and deployed to patients. Innovation has come from both the private sector, and academia, often in partnership, as well as public-private partnerships. The private sector has played a notable role in driving innovation for the de novo therapeutics that have become clinically indispensable as the pandemic progressed.

The protection of Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) has been the indispensable backbone to many of these initiatives, allowing collaboration, sharing of compound libraries, and co-operation on clinical trials between all kinds of different organisations both private and public, including commercial rivals. Manufacturing collaborations – underpinned by IPRs – have ensured that global supplies of therapeutics have been sufficient to meet demand.

A TRIPS waiver expansion to include therapeutics and diagnostics would upend this well-functioning innovation ecosystem, allowing easier compulsory licensing of proprietary technologies developed for Covid. This could not only blunt incentives for the private sector to commit resources to Covid R&D, but also for future pandemics. There is also the potential for the waiver to negatively impact R&D incentives for therapeutics and health technology platforms that have applications beyond Covid for other disease areas.

This research note looks at existing data to present evidence and arguments about the impact of the TRIPS waiver on current and future R&D efforts, both for Covid and more widely. It begins by considering drug repurposing efforts, then looks at the role of de novo innovation for Covid therapeutics. It concludes with a discussion on the impact of the waiver on current and future innovation.

Trends in Covid-19 therapeutic innovation

Although most publicly available online Covid clinical trial trackers have either gone offline or stopped being updated, there is enough historical data to ascertain some trends.

- There has been a big R&D effort directed towards Covid therapeutics: In their analysis of clinical trials launched and registered in the United States at clinicaltrials.gov between January 2020 and December 2021, Greenblatt et al, 2023[1] identified 847 unique clinical trials for Covid-19 treatments.

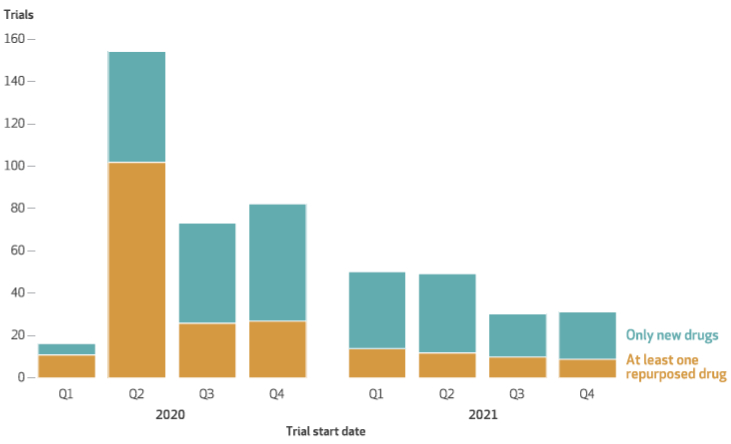

- The volume of new clinical trial registrations peaked in the early months of the pandemic (Quarters 2-4 2020) (Figure 1).

- Early R&D efforts (Q1-Q2 2020) were dominated by drug repurposing efforts, in which researchers studied existing drugs for which FDA approval had already been received for indications others than Covid-19 (Figure 1). Repurposed drugs constituted 69% of US-registered clinical trial efforts in the first quarter following the declaration of a pandemic by WHO. The relative importance of drug repurposing clinical trials compared to others declined rapidly as the pandemic progressed, dropping to 31% of US-registered trials by Q4 2021 (Greenblatt et al, 2023).

- De novo drug research became more important as the pandemic progressed, constituting 69% of clinical trials by Q4 2021 (Figure1).

Figure 1: US clinical trials for Covid-19 treatments, by drug repurposing status and quarter

The impact of the waiver on existing medicines

Drug repurposing efforts were a major focus of the research community in the early stages of the pandemic. Drug repurposing offers significant benefits as an avenue for R&D, particularly in an urgent pandemic situation: the already known safety and efficacy profiles of studied drugs avoid exposing patients to drugs with unknown risks FDA, 2013[2]; and investigators can leverage the accelerated development timelines associated with drug repurposing, for example by starting at later stages of development or using smaller samples in clinical trials Neuberger et al, 2019[3].

The promise of drug repurposing certainly played out in the context of Covid-19, with many drug repurposing trials resulting in existing drugs being included in standard of care guidelines issued by the National Institutes of Health NIH, 2020[4] and Infectious Disease Society of America Bhimraj et al, 2020[5] and United Kingdom Covid treatment clinical guidelines NICE, 2022a[6].

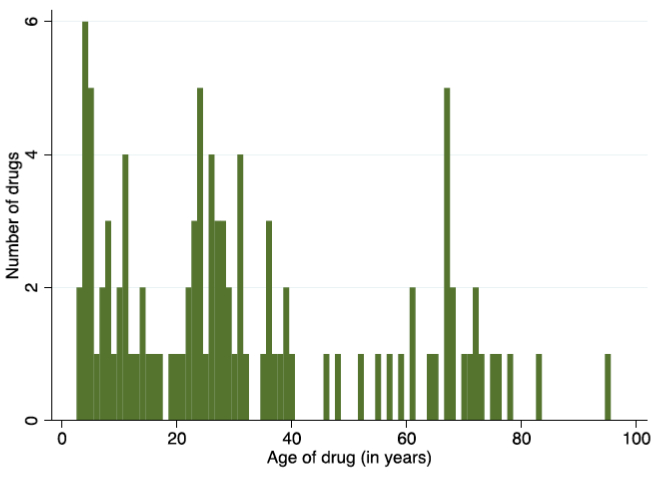

Many of these drugs are old and off-patent, with a mean age of 31 years from FDA approval to 2022 in the sample analysed by Greenblatt, Gupta, and Kao (2023). This includes therapeutic stalwarts such as dexamethasone, initially approved by the FDA in 1958, which was the subject of nine Covid-19 clinical trials between 2020 and the end of 2021. However, this average figure masks a wide variation with a considerable number of younger medicines the subject of repurposing clinical trials in the first two years of the pandemic; including 35 repurposing trials involving medicines younger than 20 years and therefore likely to still be under patent protection (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Age distribution of repurposed drugs

These trials did result in several patented medicines, with approval for other indications, making it into the official standards of care for Covid-19. The most studied existing but patented medicines are tocilizumab, an immunosuppressive drug used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (12 Covid-19 clinical trials); and baricitinib, a kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and alopecia areata (five Covid-19 clinical trials). Baricitinib has primary patents and applications filed or granted in nearly 50 jurisdictions, expiring in 2029, according to Medspal, the patent database administered by the Medicines Patent Pool[7].

To this list must also be added remdesivir, an anti-viral treatment originally developed (but did not receive approval for) Hepatitis C and Ebola. This patented medication received FDA Emergency Use Authorisation (EUA) for the treatment of Covid-19 in 2020 (FDA, 2020)[8], and has gone on to be a mainstay of hospital-based treatment for Covid-19 in many countries (NHS, 2023)[9].

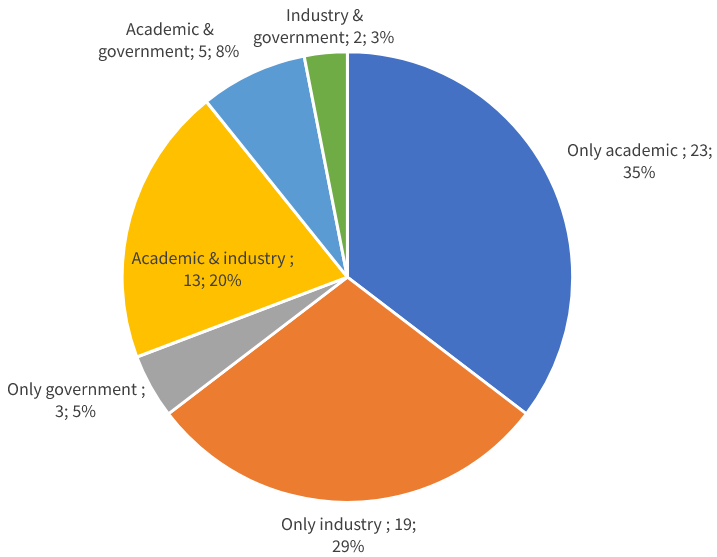

Data taken from Greenblatt, Gupta, and Kao (2023) shows that drug repurposing projects for Covid-19 that involved medicines with generic competitors were mainly sponsored by academia (n=126) with industry sponsoring far fewer (n=35). Industry was involved in partnership with industry or government in 12 further clinical trials, however.

However, drug repurposing trials for Covid-19 involving patented drugs had far greater industry involvement proportionally, with the private sector involved in 52%, often in partnership with academia (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Sponsorship of repurposing clinical trials on patented medicines

It may be that the private sector played only a small role in drug repurposing trials involving generic medicines because of the difficulties in making a financial return on R&D outlays if the product in question was already open to generic competition.

Industry had far greater involvement in repurposing trials involving existing patented medicines, however. It is a reasonable assumption that this difference is due to the existence of intellectual property rights. The ownership of patents on a medicine creates the potential of returns for rights holders. The prospect of gaining a new infectious disease franchise (such as Covid-19) for an existing patented medicine was likely a strong motivator to invest in R&D for private sector companies that ultimately must be profit-making to exist.

Intellectual property rights therefore have encouraged industry to look at their existing medicines portfolios for potential Covid-19 applications, and then invest in the R&D efforts and clinical trials required to demonstrate efficacy and safety. While bringing a new drug to market can take on average 15 years and cost between USD2bn and USD3bn, repositioning an existing drug is cheaper and quicker because pre-clinical phase 1 and occasionally Phase 2 trials can be omitted (Nosengo, 2016).[10] Nevertheless, the estimated USD300mn (Nosengo, 2016)[11] required to conduct repurposing trials is still a significant sum, and such capital is much easier for the private sector to mobilise and deploy, given the risks involved, if intellectual property rights are secure.

Based on the foregoing, we can assume an expanded waiver would have a significant impact. It would derail many drug repurposing efforts directed at Covid by introducing considerable uncertainty as to the prospect of financial return for the private sector (which has played a key role here to date). Second, it would expose patented medicines repurposed for Covid but developed for other indications to the risk of compulsory licensing.

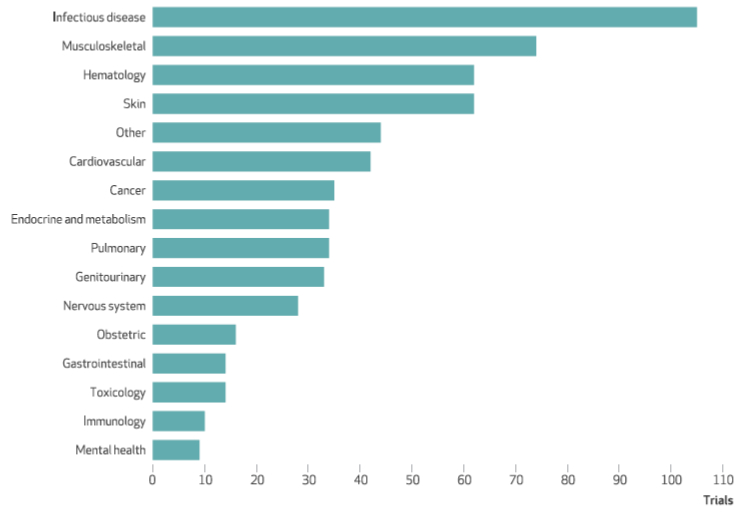

During the Covid-19 pandemic, innovation has come from unpredictable sources. While the largest number of drug repurposing trials have focused on existing infectious disease medicines, new knowledge garnered during the pandemic caused researchers to cast their net wider as the systemic impact of Covid on the body became better understood. Figure 4 shows the broad range of disease categories of US drug repurposing trials, including big showings from musculoskeletal therapeutics, especially anti-inflammatory agents initially developed for rheumatologic diseases; haematology; and skin medicines. Other categories cover medicines only very distantly related to Covid-19 such as mental health and obstetrics.

Assuming a small proportion of these drugs showed efficacy against Covid-19, this would raise the risk of compulsory licensing across a broad range of medicines currently used in other areas, some of which are very oblique to Covid.

Figure 4: Disease categories of repurposed drugs tested in US clinical trials for Covid-19 treatments, 2020-21

By injecting a good deal of uncertainty about the security of patent rights, the proposed TRIPS waiver expansion would be highly disruptive to repurposing efforts that focus on innovative, patented medicines. It would also create a perverse incentive for companies not to screen their existing compound libraries, because any compound that showed promise for Covid would immediately have questions raised as to the surety of its intellectual property rights.

A further consideration is the long-term impact of a waiver expansion on the innovation ecosystem. If patent protection had not been available originally for those drugs repurposed for Covid-19, those technologies, without which the treatments could not have been made available in such a short time, might not have been developed in the first place (Mercurio, 2021).[12] By reducing incentives now, there will inevitably be less to build on in future pandemic situations.

An adjacent point is that the diagnostics and therapeutics used for COVID-19 (such as test kits) may build upon platform technologies with actual and potential applications that go far beyond Covid. An expanded waiver presents a threat to the development and use of those applications.

For instance, emerging technologies such gene-editing technology CRISPR have a wide range of potential applications in health and agricultural biotechnology (Ledford & Callaway, 2020).[13] CRISPR has formed the basis of several Covid testing kits that have received FDA EUA, including those of Sherlock Biosciences and Mammoth Bio. Such tests have become progressively faster and more sensitive, demonstrating the potential of the technology (Service, 2020).[14]

An expanded waiver that includes Covid diagnostics could lead to the increased compulsory licensing of patents covering test kits and associated processes, such as CRISPR gene editing methods. Similarly, as discussed above, extending the waiver to therapeutics could increase compulsory licensing of compounds and associated processes with actual or potential uses beyond Covid. The question would be how to ensure that any therapeutic or diagnostic manufactured under compulsory license would only be used for the purpose of Covid: enforcement would be up to individual WTO members with companies themselves alerting the authorities. The waiver mechanism agreed in June 2022 either rendered ambiguous or eliminated entirely guardrails (including transparency requirements) that had been in place under the previous WTO compulsory licensing regime. Given existing problems with enforcement this could develop into a kind of “honour system” (Geneva Network, 2022).[15] This kind of unpredictability as to the surety of intellectual property rights could have grave implications for the development of important platform technologies, such as CRISPR, as well as categories of therapeutics that have demonstrated promise for Covid such as anti-inflammatories.

The importance of de novo therapeutic innovation for Covid

Figure 1 shows that as the pandemic progressed, de novo clinical trials came to dominate, as repurposing opportunities were already exploited, standards of care became higher, and more was learnt about Covid-19’s impact on the body. This R&D effort bore fruit, with innovative therapeutics assuming a greater importance in clinical practice as the pandemic progressed.

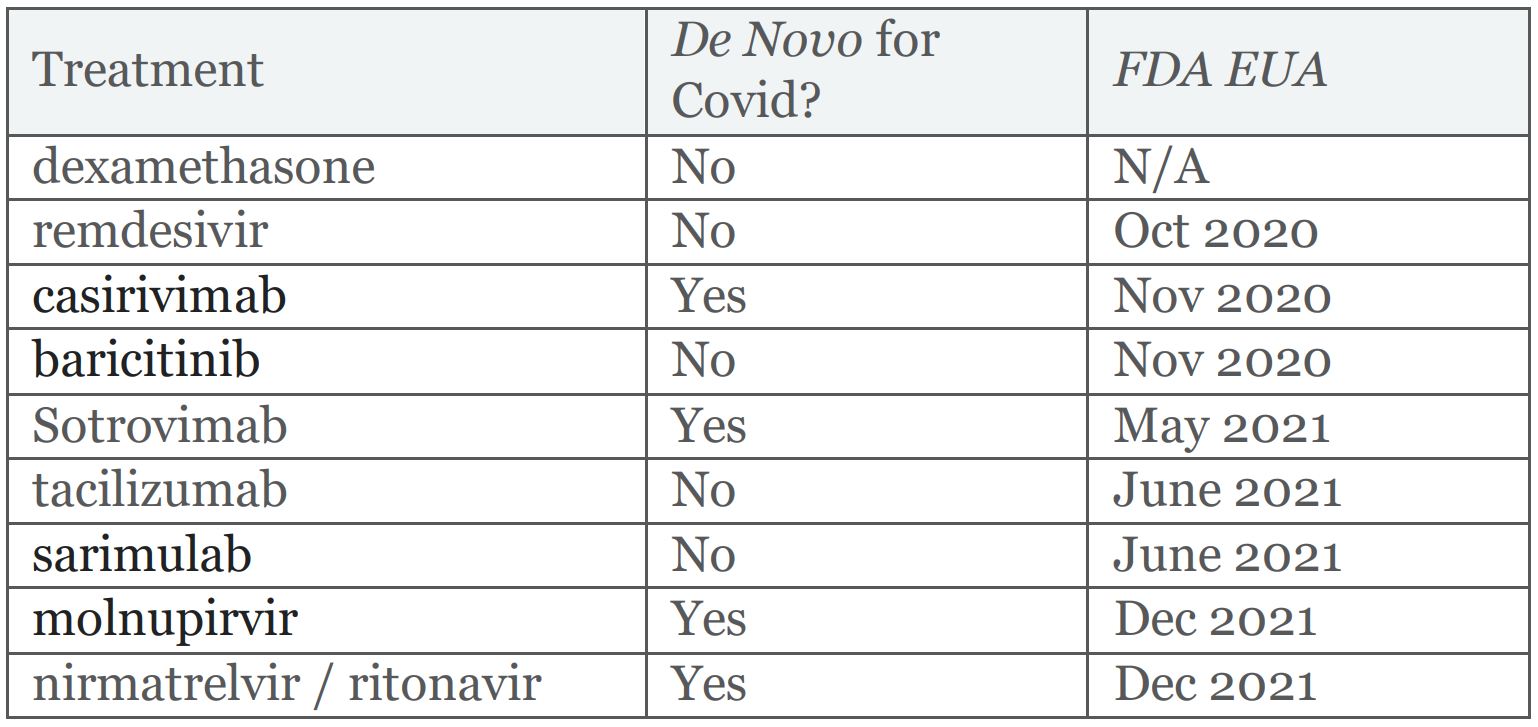

Four out of the nine medicines included in the latest United Kingdom Covid-19 treatment guidelines (July 2022), a standard of care broadly representative of developed countries, were developed originally for Covid-19 (Figure 5). A fifth innovative medicine, remdesivir, had failed to received FDA approval for Hepatitis C and Ebola, but was found to be efficacious for Covid-19 and therefore included in treatment guidelines.

A notable clinically important example is nirmatrelvir / ritonavir (Paxlovid), an anti-viral medicine used to treat early Covid-19 infection to prevent more severe symptoms. Innovative medicines such as this play an important role in helping to keep infected people out of hospital, reducing costs and burden on the overall healthcare system. Such a medicine was not available before the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Figure 5: Medicines included in United Kingdom Covid-19 standard of care (NICE, 2022b)[16]

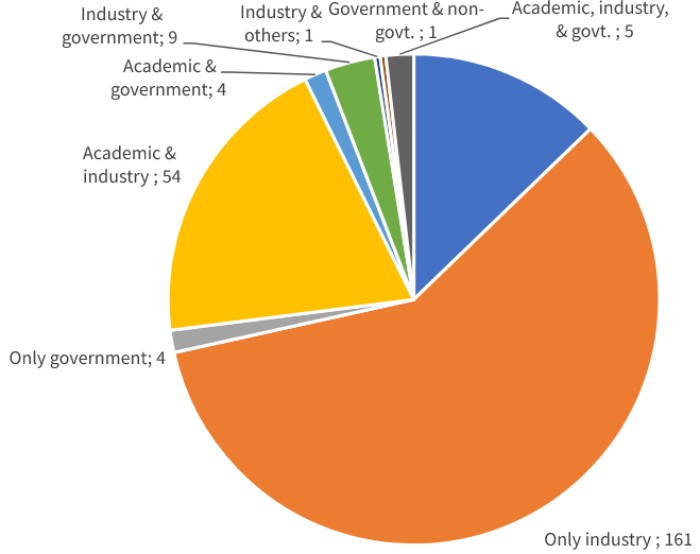

The fact that four out of the nine medicines regularly used to treat Covid-19 are de novo innovative is an impressive feat given the highly compressed R&D timelines involved. The data shows that this is largely thanks to industry, which has played the leading role for clinical trials on de novo drugs (Figure 6). Here, sole industry sponsorship constituted 59% of all trials in the sample, academic and industry partnerships 20% and industry, government and others 5.5%. Collectively, therefore, industry sponsored either solely or in partnership 84.5% of all Covid-19 clinical trials for de novo innovative Covid medicines between 2020 and the end of 2021. As we have already seen, the existence of IP rights is an imperative for industry participation in R&D, a situation which would be put into doubt by an expanded waiver.

Figure 6: Sponsorship of Covid-19 clinical trials involving de novo medicineS

IP and R&D collaboration

Another interesting artefact of Greenblatt, Gupta, and Kao’s data is the high level of R&D collaboration it shows between different entities. 20% of de novo Covid therapeutic clinical trials were between industry and academia, which is suggestive of a high level of trust between these organisations. Implicit in the data are clinical trials involving private sector partners, who could be rivals. Private sector vaccine collaborations are well known (such as Pfizer / BioNTech) and R&D collaborations have also taken place for Covid treatments. Examples include those between MSD and Ridgeback Therapeutics (molnupirvir), Roche and Regeneron (casirivimab and imdevimab), and GSK and Vir (sotrovimab) (IFPMA, 2022).[17]

IP is fundamental to such collaborations. Because patent rights require public disclosure, they enable drug developers to identify partners with the right intellectual assets such as know-how, platforms, compounds and technical expertise. Without patents most of this valuable proprietary knowledge would be kept hidden as trade secrets, making it impossible for researchers to know what is out there (Schultz, 2022).[18]

Second, the existence of laws protecting intellectual property helps rights-holders make the decision to collaborate in the first place. By allaying concerns about confidentiality, IP enables companies to open their compound libraries, and to share platform technology and know-how without worrying they are going to sacrifice their wider business objectives or lose control of their valuable assets.

For instance, rights holders might contribute IP that is useful for entirely different diseases to Covid-19 collaborations (as we have seen in this paper). IP rights and licensing ensure those rights can only be used for the agreed reason, preventing competitors freeriding to gain an unfair advantage in other areas.

Discussion

The existing IP system is presiding over a huge level of research and development activity into Covid-19 therapeutics. According to BIO, there were 205 antivirals and 305 treatments under development as of 19th September 2022 (link no longer available).

These R&D projects encompass a range of public-private partnerships and in-house programmes that would become far less viable following an expanded IP waiver. At least some of this research will likely cease if the TRIPS waiver is expanded, as investments become less secure and potential returns evaporate. As we have seen, de novo drug development clinical trials became more important as the pandemic progressed, most of which were conducted by industry, which brings to bear unique and irreplaceable skills, resources, know-how and R&D facilities. In a post waiver world, governments alone would struggle to fill these R&D gaps, given the amounts of capital and skill required.

The concern is not theoretical. A 2018 news report related that innovators had felt “burned” in past pandemics when governments reneged on promises to purchase vaccines after those pandemics turned out to be less dangerous than feared. As a result, innovators at that time were curtailing vaccine research programs and taking a more conservative approach (STAT, 2018).[19]

As the article explained, “nearly all the major pharmaceutical companies that work on these vaccines have found themselves holding the bag after at least one of these outbreaks.” They lost significant sums in the case of the H1N1 virus, after governments reneged on commitments to purchase vaccines. The result of this scepticism was that governments needed to make much more solid and substantial advanced purchase commitments for vaccines at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Covid-19 is presenting similar risks to therapeutic R&D and manufacturing. According to Airfinity data, a lack of demand means that Pfizer only produced 35% of its theoretical production capacity of Paxlovid in 2022, with MSD only producing 45% (WTO, 2022).[20]

The Covid therapeutic market is increasingly saturated with many competing products on the market and more coming onstream, including generic alternatives. This saturated market faces declining demand: Governments and NGOs purchased 35 million COVID-19 treatments for low- and middle-income countries for 2022 but have only been able to administer 10 million as of September 2022.[21]

These factors inevitably translate into declining profit margins. Add in the potential for confiscation via compulsory licensing following an expanded TRIPS waiver and the Covid therapeutic market begins to look increasingly unattractive for private sector innovators. Lessons could be drawn from this by corporate managers in the event of a future pandemic when they decide where to allocate R&D resources.

[1] Greenblatt W, Gupta C, Kao J, “Drug Repurposing During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons For Expediting Drug Development And Access”, Health Affairs, 2023 Mar;42(3):424-432. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01083

[2] US Food and Drug Administration, 2013, “Investigational new drug applications (INDs) – Determining whether human research studies can be conducted without an IND”,Silver Spring (MD): FDA; 2013 Sep

[3] Neuberger A, Oraiopoulos N, Drakeman DL. 2019,“Renovation as innovation: is repurposing the future of drug discoveryresearch?”, Drug Discov Today, 2019;24(1):1–3. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2018.06.012

[4] National Institutes of Health, 2020, “Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID- 19) treatment guidelines”, NIH, 2020, Bethesda (MD)

[5] Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH, Lavergne V, Baden L, Cheng VCC, et al. “Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients with COVID-19”, Clin Infect Dis, 2020 Apr 27;ciaa478 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa478

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022a, “Managing COVID-19: Treatments (July 2022, v27.0)”, NICE

[7] https://www.medspal.org/?keywords=Baricitinib&page=1

[8] US Food and Drug Administration, 2020, “COVID-19 Update: FDA broadens emergency use authorization for Veklury (remdesivir) to include all hospitalized patients for treatment of COVID-19”, FDA

[9] National Health Service (England), 2023, “Interim Clinical Commissioning Policy: Interim Clinical Commissioning Policy: Remdesivir for patients hospitalised due to COVID-19”, NHS

[10] Nosengo N, 2016, “Can you teach old drugs new tricks?”, Nature, 534, pp.314-316, 2016, doi: 10.1038/534314a

[11] Nosengo N, 2016, “Can you teach old drugs new tricks?”, Nature, 534, pp.314-316, 2016, doi: 10.1038/534314a

[12] Mercurio B, 2021, “WTO Waiver from Intellectual Property Protection for COVID-19 Vaccines and Treatments: A Critical Review”, Virginia Journal of International Law Online, 9-32 (2021), doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3789820

[13] Ledford H, Callaway E, 2020, “Pioneers of revolutionary CRISPR gene editing win chemistry Nobel”, Nature, 586, 346-347 (2020), doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02765-9

[14] Service, RF, 2020, “New test detects coronavirus in just 5 minutes”, Science, Oct. 8, 2020, doi: 10.1126/science.abf1752

[15] Geneva Network, 2022, “Should the TRIPs waiver be expanded to therapeutics and diagnostics”, Geneva Network, Oct. 15 2022

[16] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022b, “Managing COVID 19: treatments (May 2022 v24.0)”, NICE

[17] International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations, 2022, “Applying Lessons from Covid-19 to create a Healthier, Safer, More Equitable World”, IFPMA

[18] Schultz M, 2022, “Trade Secrecy and Covid-19”, Geneva Network

[19] STAT, 2018, “Who will answer the call in the next outbreak? Drug makers feel burned by string of vaccine pleas”, STAT

[20] Communication from Mexico and Switzerland, WTO TRIPS Council Discussions on Covid-19 therapeutics and diagnostics, November 2022, available at https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/IP/C/W693.pdf&Open=True

[21] PhRMA, 2022, “Expanding the TRIPS Waiver Is Unnecessary and Harmful”, PhRMA, by Airfinity, Sept 2022

Bibliography

Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH, Lavergne V, Baden L, Cheng VCC, Edwards KM, Gandhi R, Muller W, O’Horo JC, Shoham S, Murad MH, Mustafa RA, Sultan S, Falck-Ytter Y, 2020, “Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients with COVID-19”, Clin Infect Dis, 2020 Apr 27;ciaa478 doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa478

Geneva Network, 2022, “Should the TRIPs waiver be expanded to therapeutics and diagnostics”, Geneva Network, Oct. 15 202

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations, 2022,“Applying Lessons from Covid-19 to create a Healthier, Safer, More Equitable World”, IFPMA

Greenblatt W, Gupta C, Kao J,“Drug Repurposing During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons For Expediting Drug Development And Access”, Health Affairs, 2023 Mar;42(3):424-432. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01083

Ledford H, Callaway E, 2020, “Pioneers of revolutionary CRISPR gene editing win chemistry Nobel”, Nature, 586, 346-347 (2020), doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02765-9

Mercurio B, 2021, “WTO Waiver from Intellectual Property Protection for COVID-19 Vaccines and Treatments: A Critical Review”, Virginia Journal of International Law Online, 9-32 (2021), doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3789820

National Health Service (England), 2023, “Interim Clinical Commissioning Policy: Interim Clinical Commissioning Policy: Remdesivir for patients hospitalised due to COVID-19”, NHS

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022a, >“Managing COVID-19: Treatments (July 2022, v27.0)”, NICE

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022b, >“Managing COVID 19: treatments (May 2022 v24.0)”, NICE

National Institutes of Health, 2020, “Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID- 19) treatment guidelines”, NIH, 2020, Bethesda (MD)

Neuberger A, Oraiopoulos N, Drakeman DL. 2019, “Renovation as innovation: is repurposing the future of drug discovery research?”>, Drug Discov Today, 2019;24(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.06.012

Nosengo N, 2016, “Can you teach old drugs new tricks?”, Nature, 534, pp.314-316, 2016, doi: 10.1038/534314a

PhRMA, 2022, <“Expanding the TRIPS Waiver Is Unnecessary and Harmful”, PhRMA, by

Airfinity, Sept 2022

Schultz M, 2022, “Trade Secrecy and Covid-19”, Geneva Network

Service, RF, 2020, “New test detects coronavirus in just 5 minutes”, Science, Oct. 8, 2020, doi: 10.1126/science.abf1752

STAT, 2018, “Who will answer the call in the next outbreak? Drug makers feel burned by string of vaccine pleas”, STAT

US Food and Drug Administration, 2013, “Investigational new drug applications (INDs) – Determining whether human research studies can be conducted without an IND”, Silver Spring (MD): FDA; 2013 Sep

US Food and Drug Administration, 2020, “COVID-19 Update: FDA broadens emergency use authorization for Veklury (remdesivir) to include all hospitalized patients for treatment of COVID-19”, FDA